By: Charles Ebikeme

In February of this year we saw the launch of the first human trial for a new vaccine for visceral leishmaniasis (leishmaniasis is one of the neglected tropical diseases, and it has been blogged about it in the past here on End the Neglect).

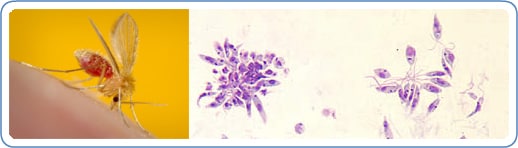

Photo credit: CDC

The new trial was launched by the InfectiousDiseaseResearchInstitute (IDRI) in Seattle, Washington with the plan to hold a further Phase 1 trial in India. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is funding the Phase 1 clinical trials, as part of the recently announced worldwide partnership with the WHO and 13 pharmaceutical companies to control or eliminate 10 neglected tropical diseases.

This new vaccine development can be added to a fast-expanding list of so-called “anti–poverty” vaccines; such as the famed RTS,S malariavaccine that last year proved to be effective (albeit not to levels some would deem completely effective), and vaccines in development for rabies, hookworm, schistosomiasis and dengue.

Visceral leishmaniasis represents one form of a disease seen across much of the old and new world — across 88 countries — and is one of the most deadly parasitic infections. In India, they refer to it after the Hindi word that means black fever — kala-azar, the black fever that haunts those infected and whose skin becomes dark and gray. Wherever it infects, kala-azar is the most deadly form of leishmaniasis.

For the sake of brevity, the history of the leishmaniasis vaccine dates back to the 1940s with “leishmanization,” as it was known, the deliberate inoculation of infective and virulent leishmania from the “exudate” of a lesion on the skin. Crude, unreproducible and wholly unsafe, the method of leishmanization eventually gave way to the first generation of vaccine research, consisting of killed or live attenuated- alive but noninfectious- parasites.

The second generation of vaccine research came much later; when we were able to genetically modify the leishmania species themselves or use bacteria or viruses as surrogates carrying leishmania genes.

Some methods rely on the identification, thanks to genome sequencing, of proteins on the parasite’s surface that can be used to elicit an immunological response. Ideally this would be a protein that is expressed in more than one life cycle stage of the parasite, so our immune systems can attack the parasites at multiple levels.

More recently, researchers learned to manipulate the leishmania genome to create genetically modified parasites. This means that researchers now have the potential to develop live attenuated parasite vaccines. This represents a powerful alternative for developing a new generation vaccine against leishmaniasis.

Elliciting an immune response to leishmania is something easier said than done. Many early vaccines that showed promise ultimately failed to do this. This is a fact made even more complicated by the fact that leishmania parasites survive within host cells, hiding and inhibiting the cell’s interior defenses.

The IDRI vaccine, known as LEISH–F3 + GLA-SE, is a highly purified, recombinant vaccine. It incorporates two fused leishmania parasite proteins and a powerful adjuvant- a molecule used to enhance vaccines- to stimulate an immune response against the parasite.

With the geographical range for leishmaniasis slowly expanding, a vaccine could not come at a better time. Spurred on by global warming, mass migration and rapid urbanization, cases are being reported in previously unaffected areas.

For all we know about the way our own immune system works, there remain large blind spots and gaps in our knowledge. The delicate balance and complexity hidden within the immune system is only made evident when diseases and germs find a way to avoid and exploit it. Vaccines are seen as the silver bullet, the game changer, sophisticated pieces of science that are so simple in their function. The possibility of a kala-azar vaccine is sweet, even sweeter if a single vaccine has the potential to protect against other leishmania diseases.

Charles Ebikeme is a writer and scientist with a research background in tropical diseases. Possessing a MSc from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, and a PhD in Parasitology from the University of Glasgow, Charles currently blogs and writes for the All Results Journals – a new publication system focusing on negative results – covering topics on the hidden side of the scientific publication process.