By Romina Rodríguez Pose, independent consultant on international development and lead author for the Health Dimension case studies, Development Progress Project.

Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) affect the poorest billion people in the world. They cause number of chronic health conditions that largely limit people’s ability to study and work and consequently have a healthy and productive life. The stigma attached to them can also lead to isolation and fear for those who suffer.

Although they have been long ignored within international and national agendas, in the last decades, there has been an increasing awareness of how NTDs can impede endemic countries from achieving broader development goals. This led to the emergence of global public-private partnerships involving major drug donations from key pharmaceutical companies, the development of inexpensive control strategies and a growing number of donors earmarking funding for integrated NTD control.

These readily available solutions have enabled some endemic countries to fight the five NTDs that bear 90 percent of the global burden: onchocerciasis, also known as river blindness; schistosomiasis, also known as snail fever; lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis; soil transmitted helminths, also known as intestinal worms; and trachoma.

To better understand the drivers of progress, ODI’s Development Progress project has taken a closer look at two of the leading performers: Sierra Leone in Africa and Cambodia in Asia. In spite of their different contexts and epidemiological profiles, three drivers have emerged in both case studies:

To better understand the drivers of progress, ODI’s Development Progress project has taken a closer look at two of the leading performers: Sierra Leone in Africa and Cambodia in Asia. In spite of their different contexts and epidemiological profiles, three drivers have emerged in both case studies:

1. Advances in the fight against NTDs have been driven by the availability of earmarked funds and donated drugs. These have been crucial for both resource-constrained countries, since most endemic countries are faced with several competing, and perhaps more urgent, health issues (such as high mortality rates for mothers and children in Sierra Leone and dengue outbreaks in Cambodia). As a counterpart, political will and local engagement to take advantage of global initiatives have been crucial in bringing NTDs within the national agenda. Both governments, through their Ministries of Health, have proactively looked for partners, secured funds and drugs donations and made important efforts to develop local capacity.

2. There is an important transitional role for development partners in providing access to strategies and guidelines on how to deal with NTDs until local capacity is fully developed. In both countries, this was achieved through bilateral, regional and global partnerships that helped build the local knowledge base for endemic countries to find their own solutions and to implement strategies according to the particular context. These dynamics between development partners and NTD programme managers have gradually led to a ‘transfer of ownership’ of the NTD programmes.

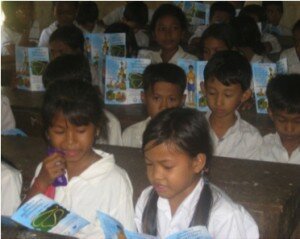

3. The integration of NTD activities within an existing government structure has been vital to set up cost-effective NTD programmes. Both countries have integrated the distribution of drugs within health and education systems. In Cambodia, given the main threat is from intestinal worms which particularly affect school-aged children, progress has been achieved by integrating the distribution of drugs into the school system and turning teachers into twice-yearly doctors/pharmacists. In Sierra Leone, given that the entire population is at risk from at least three NTDs, the main strategy involved the engagement and training of community members as drug distributors. Elected by their communities, their work is divided into catchment areas for which they are responsible, reaching the most remote corners of the country.

Despite the increasing awareness of their importance, NTDs still loom large in the cycles of poverty, ill-health and under-development that afflict too many developing countries. Yes, as Sierra Leone and Cambodia show, progress can be achieved in the most difficult contexts and with minimal resources, stressing the importance of including NTD control and elimination targets within the post-2015 sustainable development goals.

All photos by Romina Rodríguez Pose.