by: Alanna Shaikh

I just read an impressively scary article about Chagas disease. You should read it too, if you have access. It’s only eight pages long and it provides a clear glimpse into the future of communicable diseases. Once Chagas was a Latin American problem; it is now in the process of becoming global. On the off-chance you don’t have the article, or aren’t up to eight pages of journal reading , I’ll summarize it here for you.

In short, Chagas is spreading across the planet in a surprising way. The cause of this globalization is not, as you might expect, global warming (although that is increasing the natural habitat for Chagas.) Instead, the disease is being spread by emigration from Latin America. The disease has traveled with emigrants to Australia, Europe, Japan, and Canada.

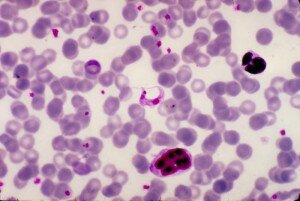

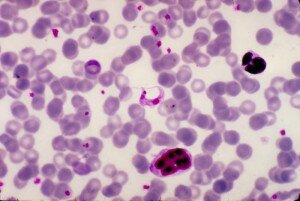

T. cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas disease, can stay dormant in the human body for years. So, when emigrants travel, the disease goes with them. It started out as a novelty – a surprise to physicians. It’s now included in standard medical screenings. The article recommends training physicians on the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease and that policymakers develop national plans for prevention and treatment.

T. cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas disease, can stay dormant in the human body for years. So, when emigrants travel, the disease goes with them. It started out as a novelty – a surprise to physicians. It’s now included in standard medical screenings. The article recommends training physicians on the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease and that policymakers develop national plans for prevention and treatment.

The article goes into more detail on the statistics of Chagas infection and transmission. They’ve got data on infection rates in Europe and Australia, broken down by the country of immigrant origin. What really interests me, though, is the trend we’re looking at here.

People move around. They travel for vacation, they take business trips, and they leave their homes in search of better prospects elsewhere. And they take their infections with them. Global air travel means the end of region-specific diseases. During the swine flu pandemic, we saw exactly how fast an infection can spread. Geographic distance is not the protection it used to be.

Right now, Chagas is still a Latin American disease, but this article, as discussed, shows that’s changing. The larger point is that other diseases are expanding, too, because of both climate change in the increased accessibility of air travel.

The wealthy world is already stepping up malaria control to stay ahead of the territorial expansion caused by climate change. Yellow fever, dengue, and encephalitis are other likely candidates for growth as the weather becomes more and more to their liking.

And that effect of climate change is exacerbated by the airplanes. Drug resistant TB is brewed in a few hot spots, like Baku, Azerbaijan, and then dispersed by travel and emigration. The WHO reported on this three years ago, looking at infection transmission in airline cabins.

Between human migration, climate change, and actual disease spread in airplanes, the NTDs aren’t going to remain tropical for long. Right now, it’s easy for wealthy countries to ignore their impact since they assume that the diseases won’t come home. That won’t be true for much longer. There is a moral imperative for the countries who can afford it to fight NTDs, but it’s increasingly obvious there is blatant self-interest as well. If we can lower disease rates in the NTD endemic countries, there will be less to transmit to everyone else.

Alanna Shaikh is an expert in health consulting, writing about global health for UN Dispatch and about international relief and development at Blood & Milk. She also serves as a frequently contributing blogger to ‘End the Neglect.”

T. cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas disease, can stay dormant in the human body for years. So, when emigrants travel, the disease goes with them. It started out as a novelty – a surprise to physicians. It’s now included in standard medical screenings. The article recommends training physicians on the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease and that policymakers develop national plans for prevention and treatment.

T. cruzi, the protozoan that causes Chagas disease, can stay dormant in the human body for years. So, when emigrants travel, the disease goes with them. It started out as a novelty – a surprise to physicians. It’s now included in standard medical screenings. The article recommends training physicians on the diagnosis and treatment of Chagas disease and that policymakers develop national plans for prevention and treatment.