The Headline: The Inter-agency and Expert Group on the Sustainable Development Goals (IAEG-SDGs) has approved the inclusion of an indicator for neglected tropical diseases (NTDs).

What are the Sustainable Development Goals?

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global targets that will define and guide the international community’s efforts to end extreme poverty, fight inequality and injustice, and create a healthier environment by 2030. They are essentially the world’s to-do list, and they were adopted by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in September.

A bit of history: The SDGs replace the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which were established in 2000 and expire this year. The MDGs accelerated progress in many of their target areas, unifying the global community behind common goals.

What’s all this about an indicator?

In addition to “targets” that establish broad objectives, the SDGs include indicators to measure success on the targets. The indicators serve as a rallying point for the global community. With so many issues competing for resources, measurable, attainable goals are critical to command attention.

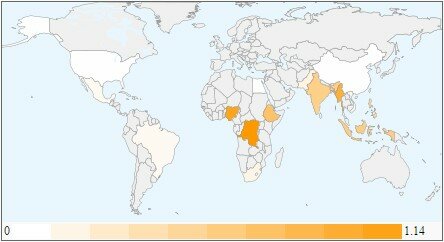

For this very reason, the NTD community has been pushing for an indicator to measure global NTD progress. More than 1.4 billion people around the world are infected with at least one NTD, but because of their low mortality rate, these diseases don’t get much attention on the global stage. However, treating NTDs is necessary to ensure that efforts to improve nutrition, education, health and economic productivity are successful. Controlling and eliminating NTDs is critical to ending extreme poverty.

The indicator, “number of people requiring interventions against NTDs,” at a meeting of the IAEG-SDG in October.

How did this happen?

NTD advocates have been pushing for an indicator for months. NTDs were little more than a footnote in the MDGs, so the NTD community has been working hard to secure some much-deserved attention in the SDGs.

The Global Network worked closely with the NTD community to advocate for this indicator, through correspondence with IAEG-SDGs members, an oral statement urging the inclusion of an indicator during a high-level meeting at the UN’s Economic and Social Council, and a community letter to all IAEG-SDGs members. END7, the Global Network’s advocacy campaign, also led three advocacy petitions urging the UN to prioritize NTDs in the SDGs.

So, we’re all good now, right?

Not quite. Once the IAEG-SDGs finishes its work, it will submit its proposed recommendations for the indicator and monitoring framework to the UN Statistical Commission. More unified advocacy from the NTD community will be needed to ensure that the final document is adopted in March 2016 without change.